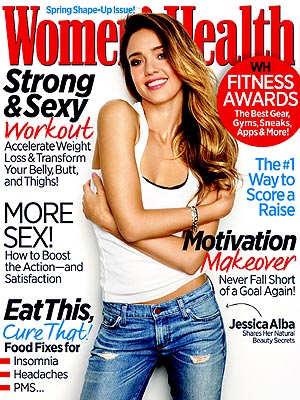

Jerome Delay/Associated Press

French armored vehicles moved toward the Niger border before making a turn to the north on Wednesday in Gao, northern Mali.

PARIS — Amid reports of continued skirmishes with Islamist extremists driven out of the main settlements of northern Mali, France renewed a promise on Wednesday that its soldiers would begin returning home within weeks, handing over authority to West African and Malian units charged with keeping the vast desert area under government control.

But French officials acknowledged that, despite their claimed military successes so far, new hostilities had erupted on Tuesday near the northern town of Gao between what were depicted as remnants of the insurgents and French and Malian forces, possibly foreshadowing a new phase in the conflict.

“From the moment our forces, supported by Malian forces, began missions and patrols around the towns which we have taken, we have encountered residual jihadist groups which fight,” Defense Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian said in a radio interview. He called the conflict a “real war.”

“We will seek them out,” he said, pledging to bring security to the recaptured areas. “Yesterday there was some rocket fire from residual jihadist groups in the Gao region,” he said, without going into detail.

In an interview published in the newspaper Metro, Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius of France said that, starting in March, “the number of French troops should fall.”

“France has no intention of remaining in Mali,” Mr. Fabius said. “It is the Africans and the Malians themselves to guarantee the security, the territorial integrity and the sovereignty of the country.”

Mr. Le Drian, the defense minister, said the French deployment for the lightning offensive launched last month had reached 4,000 soldiers, “and we won’t go beyond that.”

The deployment is far higher than the 2,500 soldiers France initially projected, and it was bolstered by the arrival over the weekend of 500 more troops.

But the French officials seemed eager to convince their citizens that the country’s armed forces were not being pulled inexorably into a perilous long-term commitment risking higher casualties.

“The progressive transfer from the French military presence to the African military presence can be made relatively quickly,” Mr. Le Drian said. “In several weeks, we will be able to begin to reduce our deployment.”

France intervened after Islamist forces who had controlled northern Mali for months began a sudden drive to the south almost a month ago. After halting the rebel advance with airstrikes, France sent in ground troops who advanced along with Malian units, apparently meeting little resistance as the insurgents seemed to melt back into their hiding places in the rugged northeast of the country.

But the latest reports of skirmishes near Gao seemed to suggest that the insurgents had not completely withdrawn.

News reports on Wednesday said that the secular National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad, a rebel movement, had claimed to control a string of small settlements in the northeast. Azawad is the name for the region used by Tuareg separatists.

In a rough tally of the casualties, Mr. Le Drian said the French intervention had killed “several hundred” insurgents, both in airstrikes and in “direct combat” in two towns in the center and north of the country: Konna and Gao.

France has said that it lost one member of its armed forces, a helicopter pilot, while Mali has said that 11 of its soldiers were killed and 60 were wounded in the fighting in Konna last month.

At the United Nations on Wednesday, France formally proposed to the Security Council that it approve a peacekeeping force for Mali in the coming weeks. Both the French ambassador, Gérard Araud, and the head of peacekeeping operations, Hervé Ladsous, said that there had to be a peace to keep before it could be deployed. “I think that we have to wait several weeks before assessing the security environment and taking the decision of deploying a peacekeeping operation,” Mr. Araud told reporters.

Although the force was originally envisioned as an African one with some United Nations backing, the planning is now focused on creating a new United Nations peacekeeping organization, but it would still rely heavily on regional troop contributions. About 2,000 soldiers from countries in the region and another 2,000 from Chad have already deployed to Mali, and they would probably become part of the United Nations force, Mr. Ladsous said. It is about half of the number of peacekeepers envisioned.

The hybrid model — deploying African troops with United Nations financial and logistics support — which was used in Darfur and Somalia, has fallen out of favor because of a lack of sufficient United Nations control over the resources it contributes. A United Nations force is “much more predictable for the actors on the ground, for the troop contributors,” Mr. Ladsous said.

Both the African Union and the regional economic bloc have endorsed the idea, but Mali, whose consent is required, has yet to sign off on the idea. There is some opposition in Mali to the idea that the peacekeeping force would be deployed not just in the north, but in Bamako as well.